Four questions to Luigi Naldini (San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, Milan) about the Nature Biotechnology study that revealed limitations and risks of gene and prime editing.

Continue reading

Four questions to Luigi Naldini (San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, Milan) about the Nature Biotechnology study that revealed limitations and risks of gene and prime editing.

Continue reading

The practice of grafting is ancient, Cato the Censor already wrote about it over two thousand years ago. CRISPR, on the other hand, is a young invention that will empower the future. A new GM-free editing strategy could blossom from the meeting of the two. Let’s call it editing by grafting. Don’t miss the paper published in Nature Biotechnology

by Friedrich Kragler’s group and Caixia Gao’s accompanying commentary. The process is shown in this video, posted on the Plamorf consortium website.

We used to imagine DNA as the book of life, the code, the Rosetta stone of Homo sapiens. But the repertoire of metaphors needs updating. Today, our species portrait has taken on the appearance of a network of nodes and relationships. Welcome to the age of the pangenome: the collective genome (pan in Greek means everything) that aspires to become more and more complex, plural, cosmopolitan and inclusive.

Continue reading

The pandemic has accelerated progress in the field of lipid nanoparticles (LNP), and now CRISPR-based treatments are set to reap the benefits.

Continue reading

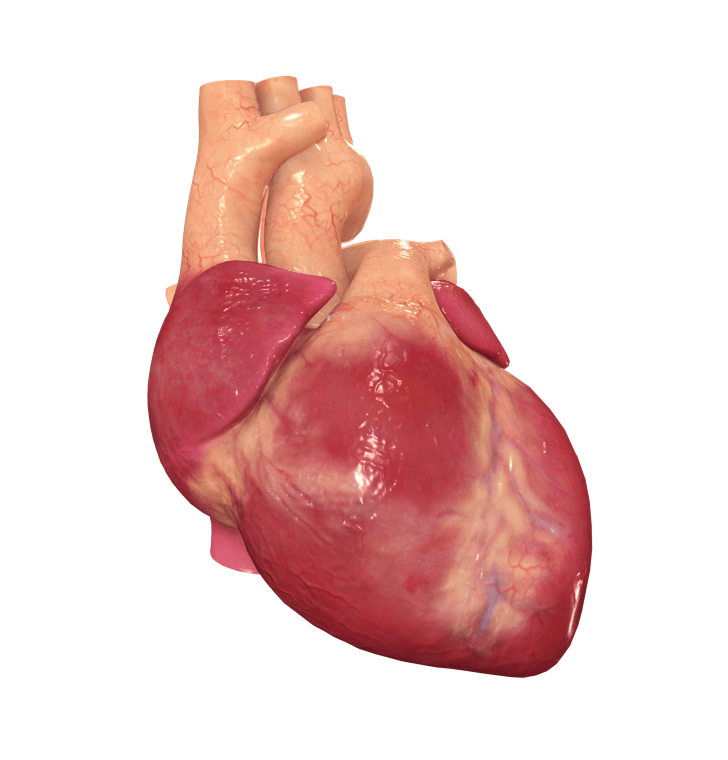

David Bennett, the first patient transplanted with a genetically edited pig heart, died on March 8 last year, two months after the surgery, presumably from a latent pig virus (a problem that does not seem hard to solve with more stringent protocols and screening, as Linda Scobie explained to me a few months ago). Since then, experimental transplants have continued in brain-dead patients who had donated their bodies to research. After xenokidneys with a single genetic modification transplanted in late 2021, in the summer of 2022 it was the turn of ten edits xenohearts. The state of the art now is that the potential of the approach still appears high, as does the morale of specialists.

Continue reading

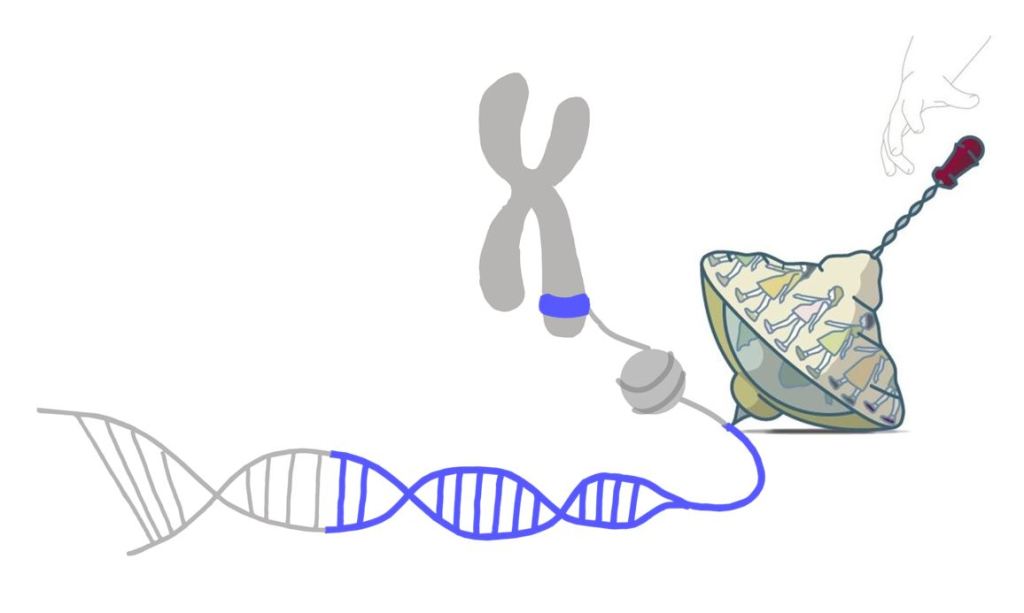

PASTE is a three-part CRISPR tool invented at the MIT McGovern Institute for Brain Research. It’s composed of a modified CRISPR-Cas9 (it’s called nickase because it nicks a single DNA strand instead of cutting both) and two effectors: RT stands for reverse transcriptase (just like in prime editing) while LSR means large serine recombinase.

This brand-new molecular machine writes the genome in three steps. Step 1: the nickase finds the desired site. Step 2: the reverse transcriptase inserts a landing pad. Step 3: the recombinase lands there and delivers its large DNA cargo. The aim is to replace whole genes, when fixing mutations is not enough (one example is cystic fibrosis). Here are the links to learn more:

Continue reading

The seminal paper by Doudna & Charpentier was published online at the end of June 2012. The printed issue came out a few weeks later, on August 17 (don’t try to buy it, Science VOLUME 337|ISSUE 6096 is out of stock). No wonder the gene-editing community is in the mood for celebration these days. If you are too, don’t miss the chance to read these articles on CRISPR’s ten-year anniversary!

Continue reading

If you like healthy food and biotechnology, you’ll love the news. Japan has given the go-ahead to market two CRISPR-edited fishes: a tiger puffer and a red sea bream, both developed by Regional Fish Co. together with Kyoto University and Kindai University.

Continue reading

As you probably know, on January 7 at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore a 57 years old man named David Bennett became the first human to have his heart replaced with that of a CRISPRed pig. But what does make a xenoheart suitable for transplantation?

Continue reading

Lulu and Nana are three years old. Amy is the name Nature Biotechnology uses to refer to the third CRISPR baby, born in late spring-early summer 2019. Their health is a closely held secret, that Vivien Marx has investigated for the journal’s December issue. “A full understanding of the health risks faced by the children due to their edited genomes may lie beyond the reach of current technology”, she writes. Despite or maybe because of that, the news feature is well worth reading. Below are a few points:

Continue reading