It is Science but it could be mistaken for The CRISPR Journal. The latest issue indeed runs three papers by three CRISPR aces – David Liu, Jennifer Doudna, and Feng Zhang – about the cutting-edge fields of biological recorders and advanced diagnostic tests. Continue reading

It is Science but it could be mistaken for The CRISPR Journal. The latest issue indeed runs three papers by three CRISPR aces – David Liu, Jennifer Doudna, and Feng Zhang – about the cutting-edge fields of biological recorders and advanced diagnostic tests. Continue reading

Category Archives: News

CRISPR latest edition

![crispr-latest-edition[8047]](https://mycrispr.blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/crispr-latest-edition8047.jpg?w=584) There is hardly any day without CRISPR news. February starts with researchers correcting abnormalities associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Science Advances) and performing allele-specific editing in blind mice (bioRxiv, forthcoming in The CRISPR Journal). A repechage from January also: how to get pluripotent stem cells by CRISPRing just one gene (Cell Stem Cell).

There is hardly any day without CRISPR news. February starts with researchers correcting abnormalities associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Science Advances) and performing allele-specific editing in blind mice (bioRxiv, forthcoming in The CRISPR Journal). A repechage from January also: how to get pluripotent stem cells by CRISPRing just one gene (Cell Stem Cell).

Evolving high fidelity CRISPR

credit Alessio Coser

It’s called evoCas9, and it’s the most accurate CRISPR editing system yet, according to a study just published in Nature Biotechnology. Researchers at the University of Trento, in northern Italy, induced random mutations in vitro on a piece of a bacterial gene coding for the DNA-cutting enzyme (the REC3 domain of SpCas9) and then screened the mutated variants in vivo in yeast colonies by looking at their color. If the molecular scissors work properly, cutting only the right target, the yeast becomes red, but colonies are white if CRISPR cuts off target. Continue reading

What if the human body attacks CRISPR? Can we cheat it?

“Uh Oh. CRISPR might not work on people”. A title like this on the MIT Technology Review website is not the best way to kick-start the new year. But wait, our motto still stands: keep calm and crispr on.

“Uh Oh. CRISPR might not work on people”. A title like this on the MIT Technology Review website is not the best way to kick-start the new year. But wait, our motto still stands: keep calm and crispr on.

The gene corrector in Nature’s top 10

2017 brightest star in CRISPR heavens is David Liu, according to Nature. Be sure not to miss this old profile from the Harvard Gazette if curious to see his funny side.

Epigenetic editing hits hat-trick

Reversing three genetic diseases in the animal model without even changing a single DNA letter. A Salk Institute team did it by bringing together two of biomedicine’s hottest trends. One is the CRISPR technique, which edits target genes through a programmable molecular machine named Cas9. The other is epigenetics, i.e., the study of chemical modifications that switch genes on and off without altering their sequence. It’s called epigenetic editing, because corrections are precise as in manuscript revision and occur at a level that is over (epi- in Greek) genetics. Continue reading

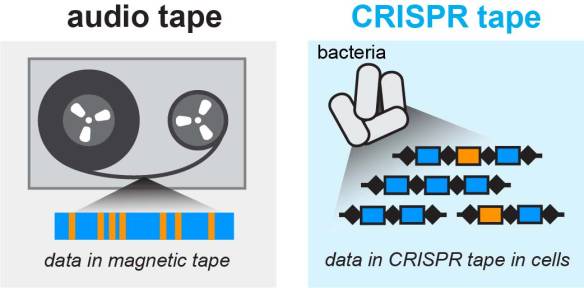

Rec-Stop-Play: CRISPR becomes a biological recorder

When using a standard tape recorder you just have to press the buttons. Now a Columbia University team has devised a system for doing the same in living systems, recording changes taking place inside the cells. How does it work? This biological recorder, described in a study appearing in Science, is called TRACE and may help us chronicle what happens in open settings such as marine environments or in habitats difficult to access such as the mammalian gut. It records molecular fluctuations instead of sounds, capturing metabolic dynamics, gene expression changes and lineage-associated information across cell populations. The medium is DNA rather than magnetic tape. Sequencing is like playing. But how is the DNA recording done? Continue reading

When using a standard tape recorder you just have to press the buttons. Now a Columbia University team has devised a system for doing the same in living systems, recording changes taking place inside the cells. How does it work? This biological recorder, described in a study appearing in Science, is called TRACE and may help us chronicle what happens in open settings such as marine environments or in habitats difficult to access such as the mammalian gut. It records molecular fluctuations instead of sounds, capturing metabolic dynamics, gene expression changes and lineage-associated information across cell populations. The medium is DNA rather than magnetic tape. Sequencing is like playing. But how is the DNA recording done? Continue reading

CRISPR Express: nanovectors are coming

![nanoparticle MIT[1423]](https://mycrispr.blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/nanoparticle-mit1423.jpg?w=584) Suppose you have developed the winning weapon to defeat certain genetic diseases by reliably correcting pathogenic mutations. There is still a problem: how do you march onto the battlefield, inside sick cells? The weapon is the genome-editing machinery, and the most efficient vessel ever tested are lipid nanoparticles. With this approach, described in a study published in Nature Biotechnology last week, CRISPR has beaten its success record in adult animals, knocking out the target gene in about 80% of liver cells. Continue reading

Suppose you have developed the winning weapon to defeat certain genetic diseases by reliably correcting pathogenic mutations. There is still a problem: how do you march onto the battlefield, inside sick cells? The weapon is the genome-editing machinery, and the most efficient vessel ever tested are lipid nanoparticles. With this approach, described in a study published in Nature Biotechnology last week, CRISPR has beaten its success record in adult animals, knocking out the target gene in about 80% of liver cells. Continue reading

Two big cheers for base editing

The rising star of base editing shadowed classic genome editing last week. I’m sure you heard about the ground-breaking papers respectively published by David Liu and Feng Zhang in Nature and Science. CRISPR enthusiasts have probably already enjoyed the piece by Jon Cohen on the new approach, i.e., the rearrangement of atoms in individual DNA letters to switch their identity without even cutting the DNA strands. But let’s take a look also at The Scientist, which runs two must-read articles about the details of the experiments. The first take-home message is the latest achievements are exciting, but base editors are not better than CRISPR, they’re just different. The second one, there is still room for improvement with base editing, and the best is yet to come.

3 questions on CRISPR butterflies

Biodiversity is a wonderful interplay between genetics and evolution, and butterflies are a fascinating example with their variety of patterns and colors. Understanding how the same gene networks engender visual effects so diverse in thousands of Lepidoptera species is a longtime ambition for many entomologists and evolutionary biologists. The good news is that scientists nowadays have a straightforward technique working with organisms that were difficult to manipulate with conventional biotech tools. Obviously, we are talking about CRISPR. Two papers published in PNAS last week describe how genome editing was used to alter the genetic palette of colors in butterflies and how their wings changed as a result. We’ve asked the entomologist Alessio Vovlas, from the Polyxena association, to comment these stunning experiments. Continue reading

Biodiversity is a wonderful interplay between genetics and evolution, and butterflies are a fascinating example with their variety of patterns and colors. Understanding how the same gene networks engender visual effects so diverse in thousands of Lepidoptera species is a longtime ambition for many entomologists and evolutionary biologists. The good news is that scientists nowadays have a straightforward technique working with organisms that were difficult to manipulate with conventional biotech tools. Obviously, we are talking about CRISPR. Two papers published in PNAS last week describe how genome editing was used to alter the genetic palette of colors in butterflies and how their wings changed as a result. We’ve asked the entomologist Alessio Vovlas, from the Polyxena association, to comment these stunning experiments. Continue reading