Sapiens vs Neanderthalized brain organoids (credit A. Muotri)

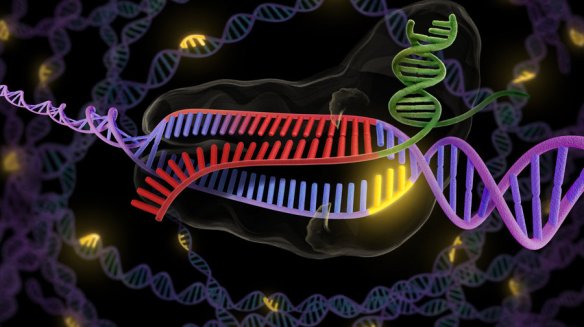

Taking a peek into the brain of a Neanderthal specimen would be a dream for whoever is interested in the evolution of human intelligence. To get an idea of the cognitive abilities of our closest relatives, so far, anthropologists and neuroscientists could only study the fossil and archaeological record, but a new exciting frontier is opening up where paleogenetics meets organoids and CRISPR technologies. By combining these approaches, two labs are independently developing mini-brains from human pluripotent stem cells edited to carry Neanderthal mutations. Alysson Muotri did it at UC San Diego, as Jon Cohen reported in Science last week. Svante Pääbo is doing it at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, as revealed by The Guardian in May. Forget George Church’s adventurous thoughts on cloning Neanderthals. The purpose here is to answer one of the most captivating questions ever asked: did the mind of these ancient men and women, who interbred with our sapiens ancestors before going extinct, work differently from ours? Last but not least, with respect to the ethics of experimenting with mini-brains, don’t miss the perspective published in Nature.

They are not super-corals genetically edited to repopulate the reef. However, the Acropora millepora described in

They are not super-corals genetically edited to repopulate the reef. However, the Acropora millepora described in  It is Science but it could be mistaken for The CRISPR Journal. The latest issue indeed runs three papers by three CRISPR aces – David Liu, Jennifer Doudna, and Feng Zhang – about the cutting-edge fields of

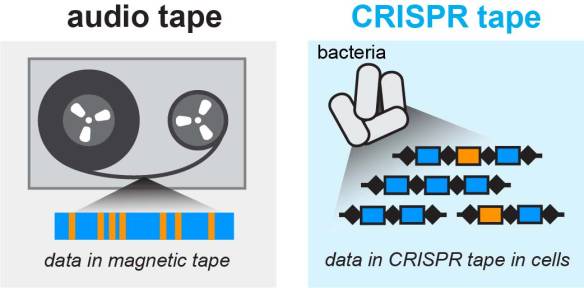

It is Science but it could be mistaken for The CRISPR Journal. The latest issue indeed runs three papers by three CRISPR aces – David Liu, Jennifer Doudna, and Feng Zhang – about the cutting-edge fields of  When using a standard tape recorder you just have to press the buttons. Now a Columbia University team has devised a system for doing the same in living systems, recording changes taking place inside the cells. How does it work? This biological recorder, described in a

When using a standard tape recorder you just have to press the buttons. Now a Columbia University team has devised a system for doing the same in living systems, recording changes taking place inside the cells. How does it work? This biological recorder, described in a  The genome-editing pioneer ponders the future of life sciences in

The genome-editing pioneer ponders the future of life sciences in

Biodiversity is a wonderful interplay between genetics and evolution, and butterflies are a fascinating example with their variety of patterns and colors. Understanding how the same gene networks engender visual effects so diverse in thousands of Lepidoptera species is a longtime ambition for many entomologists and evolutionary biologists. The good news is that scientists nowadays have a straightforward technique working with organisms that were difficult to manipulate with conventional biotech tools. Obviously, we are talking about CRISPR. Two papers published in PNAS last week describe how genome editing was used to alter the genetic palette of colors in butterflies and how their wings changed as a result. We’ve asked the entomologist Alessio Vovlas, from the Polyxena association, to comment these stunning experiments.

Biodiversity is a wonderful interplay between genetics and evolution, and butterflies are a fascinating example with their variety of patterns and colors. Understanding how the same gene networks engender visual effects so diverse in thousands of Lepidoptera species is a longtime ambition for many entomologists and evolutionary biologists. The good news is that scientists nowadays have a straightforward technique working with organisms that were difficult to manipulate with conventional biotech tools. Obviously, we are talking about CRISPR. Two papers published in PNAS last week describe how genome editing was used to alter the genetic palette of colors in butterflies and how their wings changed as a result. We’ve asked the entomologist Alessio Vovlas, from the Polyxena association, to comment these stunning experiments.  In

In  This week our journey among leading labs takes us to meet a pioneer of gene silencing. Pino Macino contributed to the birth of RNA interference, a field awarded a Nobel prize in 2006, and teaches cell biology at Sapienza University of Rome. He thinks CRISPR is a great leap forward in understanding the function of genes.

This week our journey among leading labs takes us to meet a pioneer of gene silencing. Pino Macino contributed to the birth of RNA interference, a field awarded a Nobel prize in 2006, and teaches cell biology at Sapienza University of Rome. He thinks CRISPR is a great leap forward in understanding the function of genes.