See you in September with fresh CRISPR news!

Image

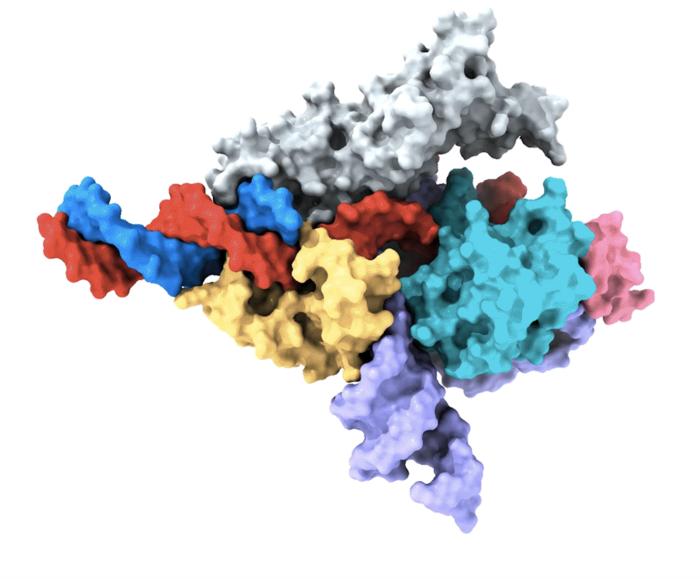

Treasure hunting in fungi and clams has led to the discovery of CRISPR-like proteins that can be RNA-programmed to edit human DNA.

“Nature doesn’t make jumps,” claimed many thinkers of the past, but modern-day geneticists can point to many exceptions to the rule. Transposons are mobile genes par excellence jumping from one point to another in the genome. In particular those associated with the OMEGA system, discovered two years ago in bacteria, head for chosen landing spots thanks to a kind of programmable GPS similar to CRISPR.

The news is that now such a phenomenon has also been detected in organisms with nucleated cells, so-called eukaryotes which include fungi, plants and animals. Feng Zhang’s group has already started engineering these programmable proteins, known as Fanzor, to turn them into efficient editing tools. Please see the paper in Nature, the article posted on the Broad Institute website and Zhang’s tweets.

The European Commission is collecting comments on the proposed regulation on New Genomic Techniques (NGTs) presented on 5 July. On this page you will find all the documents you need to form an opinion: from the criteria for establishing when a NGT plant is comparable to a conventional plant, to calculations on the costs of coexistence for organic producers (see in particular the Impact assessment report). The feedback received during the consultation period (8 weeks, extendable) will be summarised by the European Commission and presented to the European Parliament and the Council to feed into the legislative debate. In general, CRISPeR Frenzy appreciates the proposed regulation, especially for its focus on the promised benefits of NGTs in terms of environmental sustainability.

Jennifer Doudna’s Innovative Genomic Institute has received $70 million to explore a bold idea: combating climate change and other emergencies by modifying the microbial communities that live outside and inside us.

Bacteria are the true masters of the planet, for better or worse. Besides affecting our health in many ways, they are responsible for much of the methane emissions. This gas traps heat far more than carbon dioxide and is produced in large quantities by microbes that proliferate in environments associated with human activities (farms, landfills, rice paddies). The good news is that methane is short-lived, so reducing its emissions would have a rapid and substantial effect on global warming. What tools do we have at our disposal to try to pursue such an ambitious goal?

Continue reading

There is great disorder under the heavens of new biotechnology. Judging by the Italian debate on genetic innovation in agriculture, it seems that we no longer know what to call what. We are waiting for the European Commission to present its proposal to regulate ‘new genomic techniques’ (NGTs) on 5 July (see the leaked draft here). But in the meantime, on 9 June, the Italian Parliament approved a regulation in favour of experimentation with ‘assisted evolution techniques’ (TEAs), which are the same thing. However, if you read the official wording (9 bis, drought decree law) this expression is missing: instead, it refers to the deliberate release into the environment for experimental purposes of ‘organisms produced by genome editing techniques through site-directed mutagenesis or by cisgenesis’.

Continue reading

The European Commission’s proposal for an updated regulatory framework for New Genomic Techniques is due on 5 July, but someone leaked the confidential document online. In a nutshell, if the modification could also have been achieved naturally or by conventional methods, and the plant has the same risk profile as its conventional counterpart, it should be treated similarly to conventional plants and differently from GMOs (it would not require authorisation, risk assessment, traceability, labelling as GMO, but would be placed in a transparency register). For plants in which editing or cisgenesis has led to results that differ from conventional ones, the current GMO rules apply. You can read the Genetic Literacy Project’s explanation here.

Please note a couple of things environamental NGOs and organic producers should like: herbicide-tolerant NGT plants would remain subject to GMO rules, and all NGT plants would remain subject to the prohibition of use of GMOs in organic production.

The practice of grafting is ancient, Cato the Censor already wrote about it over two thousand years ago. CRISPR, on the other hand, is a young invention that will empower the future. A new GM-free editing strategy could blossom from the meeting of the two. Let’s call it editing by grafting. Don’t miss the paper published in Nature Biotechnology

by Friedrich Kragler’s group and Caixia Gao’s accompanying commentary. The process is shown in this video, posted on the Plamorf consortium website.

The progress of the new therapies of the CRISPR era can be told by interweaving two stories. The first is the one featuring Victoria, Carlene, Patrick, Alyssa, Terry and many others. There are over two hundred patients who have so far undergone some experimental treatment based on genome editing, i.e. the targeted correction of DNA instead of the addition of extra genes as in classical gene therapy. These women and men suffering from serious diseases had to face increasing pain and sacrifice until they decided to pin their hopes on a new type of experimental therapy, which is promising but not without risks. For the unluckiest of them, this act of courage and faith in science was not enough, but for many of these pioneers, life really did change. In fact, there are already dozens of people who have managed to free themselves (hopefully in the long term) from the burden of a rare genetic disease or, in some cases, leukaemia. Along with genetically edited cells, a new normalcy has arrived for them and the chance to finally think about the future.

Continue reading

The death of pioneer patient Terry Horgan is a warning about the risks of viral vectors but the focus is now on the first gene therapy being approved in the US

On the chellenging frontier of advanced therapies, every death is a pain from which everything possible must be learned. The inauspicious outcome of the individual treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy developed by the non-profit Cure Rare Disease for Terry Horgan, and tested solely on this American boy, can teach little about the specifics of CRISPR. Indeed, the death occurred before the molecular editing machine could get into action. But the information on the case, circulated in May on a preprint archive awaiting peer-reviewed, is nonetheless a valuable contribution to the advancement of knowledge in an area where science has no intention of giving up.

Continue reading