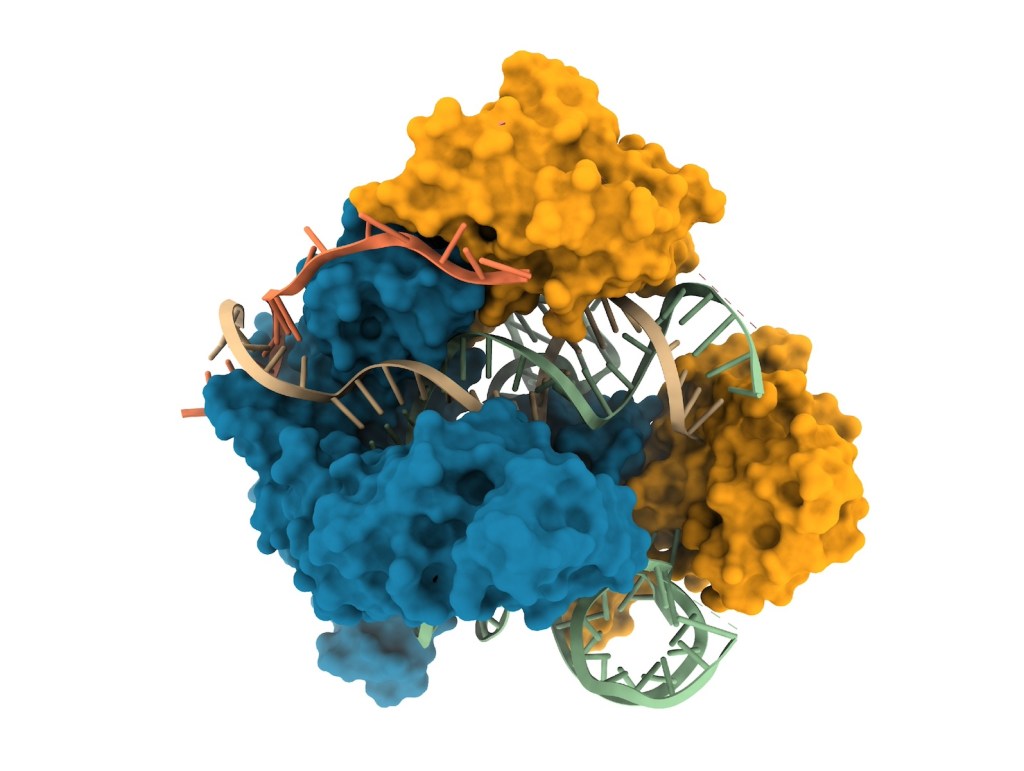

Imagine throwing a trillion darts and having every single one hit the bullseye. Achieving this level of precision in gene editing would require highly intelligent delivery of the molecular machinery for DNA repair (CRISPR or one of its variants) into patients’ bodies, reaching only defective cells while bypassing healthy tissues. The benefits would be substantial: maximum therapeutic efficiency, zero waste, and reduced risks in terms of toxicity, immunogenicity, and unwanted mutations. How can such precise targeting be achieved? By acting on multiple levels, explain Jennifer Doudna and three researchers from her Innovative Genomics Institute. See their review article, Targeted delivery of genome editors in vivo in Nature Biotechnology.