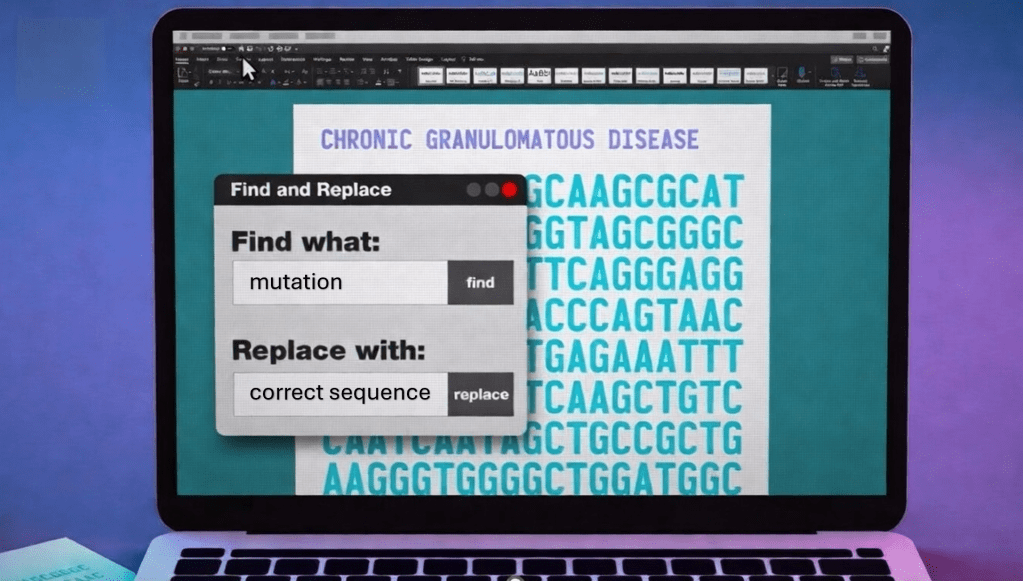

It had never happened before that a company decided to submit a commercial authorization request for a therapy tested on only two people.

We do not know the name of the teenager from Vancouver who, a year ago, became the first person in the world to receive a treatment based on a genetic correction approach similar to Word’s “find and replace.” What we do know is that before becoming a pioneer patient, even a common cold represented a serious threat to him. The father of the technique known as prime editing, David Liu, now describes him as “healthy, stable, and living with a functioning immune system.” Seeing him on skis in the the snow in the photo published by the Canadian Institutes of Health, is worth more than many words. The American National Institutes of Health, for their part, confirm that the second patient treated is also doing well.

Continue reading