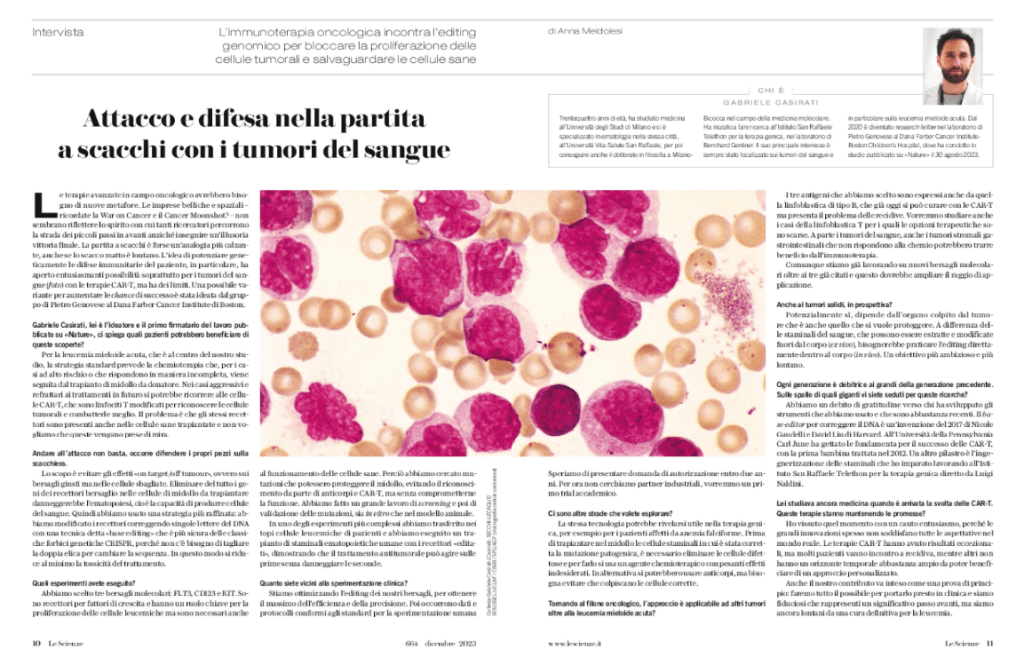

Advanced cancer therapies would need new metaphors. War and space efforts – do you remember the War on Cancer and the Cancer Moonshot? – do not seem to reflect the spirit with which so many researchers pursue the strategy of small steps forward rather than chasing an illusory ultimate victory. The game of chess is perhaps a more fitting analogy, although checkmate is a long way off. The idea of genetically enhancing a patient’s immune defenses, in particular, has opened up exciting new possibilities especially for blood cancers (Car-T therapies) but is not without its limitations. One possible variant to increase the chances of success has been devised by Pietro Genovese’s group at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston and described in Nature a few months ago. If you can read Italian, please see also the December 2023 issue of Le Scienze, with my interview to Gabriele Casirati, first author of the Nature’s paper.