Two years after Casgevy received commercial approval, only around sixty people with sickle cell disease or thalassemia have been able to benefit from it, due to a technical hurdle that the next generation of treatments will attempt to overcome

The green light from Europe came on February 13, 2024, a few months after approval in the United Kingdom and the United States. The world’s first CRISPR therapy – Casgevy, also known as exa-cel – has rightly been celebrated as a historic milestone. It was always expected that the complexity of the treatment would slow its adoption, but the numbers recently reported by STAT are nevertheless disappointing.

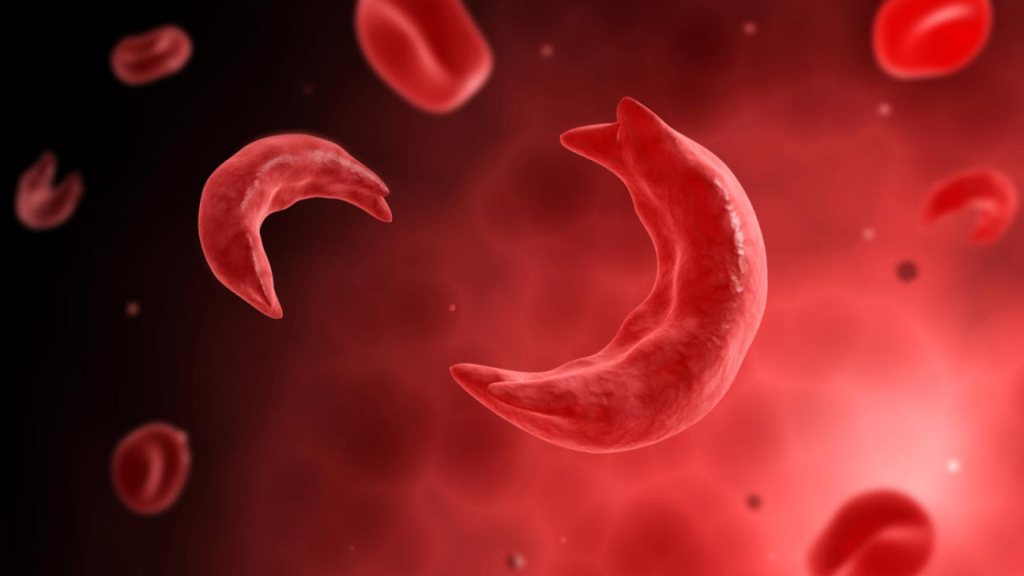

Combining Europe, the United States, and the Middle East, just over sixty people have been treated with the product developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals together with CRISPR Therapeutics. This is a remarkably low figure, considering that experts had previously estimated that around 32,000 American and European citizens could be candidates for the treatment, 25,000 of whom for sickle cell disease. All things considered, Casgevy is struggling even to keep pace with the (also slow) adoption rate of conventional gene therapy for sickle cell disease and thalassemia (Lyfgenia by Genetix), which involves inserting an additional gene rather than fixing the patient’s original DNA. What happened?

To explain this, we must first recall that we are dealing with “ex vivo” therapies, which involve collecting a patient’s cells (hematopoietic stem cells), genetically modifying them in the laboratory, and then reinfusing them after eliminating the defective counterpart inside the body (myeloablation). Paradoxically, it is the first step – the one that would seem the most routine – that has proved unexpectedly difficult. In order to collect a sufficient number of cells to initiate Casgevy treatment, some patients have had to undergo as many as five separate hospital admissions, and a small percentage have dropped out of the process altogether.

Once completed, the treatment delivers excellent results, freeing patients from extremely painful crises and other serious complications that severly shorten life expectancy. But the entire process, in addition to being expensive (around 2 million dollars per patient), has a duration that is hard to predict and sometimes very long. Between waiting periods and hospitalizations, it can take more than a year.

The first problem is that the collection relies on procedures that work well for harvesting stem cells from patients who require cell transplants for other conditions, but not in cases of sickle cell disease. To “mobilize” stem cells from the bone marrow into the bloodstream, physicians typically use two drugs, but only one of them can be used safely in patients with this disease, in which red blood cells take on their characteristic sickle shape and can block blood vessels. The cells must then be collected using an apheresis machine, which is designed for people with normal red blood cells. In practice, the centrifuge that separates blood components creates different bands in the presence of deformed cells.

Another obstacle stems from the fact that producing the CRISPR treatment requires a larger number of stem cells than conventional gene therapy. The Casgevy protocol, in fact, calls for CRISPR molecular scissors to enter the target cells after they have been made permeable by an electric pulse, instead of using a viral shuttle as in traditional gene therapy. This procedure, known as electroporation, can damage a fraction of the cells, and the cutting of the double helix can kill others, leaving relatively few intact and gene-edited cells.

It should be noted that over the months the collection procedures have become more efficient, but according to some specialists it is likely that Casgevy will be supplanted in the near future by more advanced editing treatments. In 2027, approval is expected for a competing therapy developed by Beam Therapeutics (BEAM-101, or risto-cel), which should offer an advantage. The goal remains the same – compensating for defects in adult hemoglobin by reactivating the production of fetal hemoglobin – but while the first protocol achieves this by cutting the double helix, the second relies on a more delicate approach, involving targeted DNA correction that does not require severing both strands (base editing).

Casgevy, then, has secured its place in the history books of medicine as the first drug of the CRISPR class, but it will likely not be long before, in hospitals, it has to pass the baton to the next technology, already dubbed CRISPR 2.0.