Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes. The record-holder among animals (a butterfly called Polyommatus atlantica) can boast 229. Some plants have even more, but only because their genomes have undergone multiple rounds of duplication. We’re talking about chromosomes, of course. Their number is characteristic of each species and still shrouded in mystery. Why that number? And what would happen if we changed it?

In animals, the effects tend to be detrimental: mice with fused chromosomes, for instance, show abnormalities in behavior, growth, and fertility. Plants, however, appear surprisingly flexible, as demonstrated by a new experiment using CRISPR, recently published in Science.

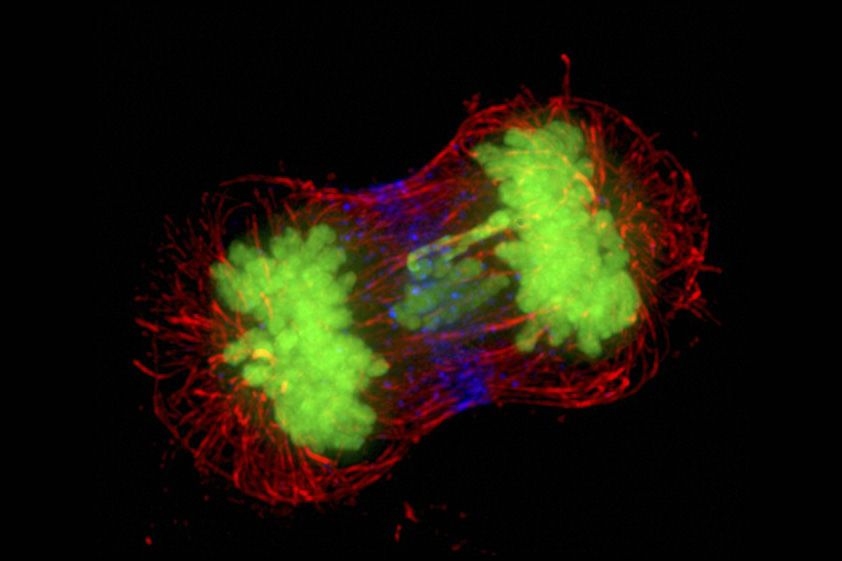

The team led by Holger Puchta in Germany managed to fuse entire chromosomes in the model species Arabidopsis, reducing its chromosome complement from ten to eight. The resulting plants developed normally, with no detectable changes in growth rate, leaf shape, root length, or seed characteristics, almost as if nothing had happened. The only trace of the intervention was found in meiosis, the cell division that produces sex cells, where crossover events were redistributed to compensate for the new chromosomal architecture.

Even in a simple organism like yeast, chromosomal rearrangements usually cause significant consequences, from cellular stress to growth defects. So what accounts for the genomic flexibility of plants? The answer likely lies in their evolutionary past, marked by repeated cycles of whole-genome duplication followed by phases of “genetic pruning.”

The new Science study is notable because it opens the door to manipulating chromosome number in diverse organisms, whether driven by pure curiosity or by the search for practical applications. Understanding how rearrangements work, and exploiting that knowledge, could prove useful for improving agronomic traits, especially when those traits reside in regions with low recombination frequency.

It’s worth remembering that phenomena similar to the experimentally induced changes seen by Puchta and colleagues also occur in nature. Such rearrangements can limit gene flow between populations of the same species and, ultimately, help turn them into distinct species. As genome-editing pioneer Feng Zhang and Kelly Dawe note in the perspective accompanying the Science paper, changes in chromosome structure and number disrupt the pairing required to produce functional gametes. Mules, for example, are healthy hybrids, but the mismatch in chromosome number between their parents (a mare and a donkey) renders them sterile.

Indeed, the researchers found that crosses between the structurally altered Arabidopsis lines and “normal” ones show reduced fertility. With a few additional steps, it may become possible to achieve complete hybrid sterility. Such a property could have useful applications for biocontainment, limiting gene flow between genetically modified crops and their wild relatives.