A year after the European Parliament voted to ban patents, EU countries still seek a compromise on NGT regulation

The revision of the regulatory framework for genetically modified plants currently underway in Europe aims to keep pace with technological advances and support the development of sustainable agriculture. The scientific community, the seed industry, and major farmers’ associations view the overall framework positively, but the devil is still in the details.

Let’s suppose a tomato variety has been edited using CRISPR: it contains no foreign DNA and carries only a favorable mutation that — with a hefty dose of luck — might have occurred naturally. Suppose this mutation helps protect the plant from disease, thus reducing the need for chemical treatments, or strengthens its drought resilience. This new kind of tomato would be indistinguishable from a conventional plant and should be regulated accordingly, without falling under the restrictions set for classic GMOs, which instead contain genes from different species. One question remains: when it comes to the legal protection of this new variety, should it be subject to biotech patents like those for GMOs, or should we apply the “plant breeders’ rights” used for varieties developed through traditional methods?

The issue is both practical and symbolic. Practical because the type of protection granted to breeders will affect innovation incentives and access to improved varieties. Symbolic because combining the words “biotechnology” and “patents” immediately raises fears of knowledge privatization and monopolies over agri-food resources.

The European Commission had carefully avoided mixing these matters in its 2023 proposal for regulating new genomic techniques (NGTs). Regulatory approval is intended to ensure consumer and environmental safety, while intellectual property deals with the economic rights of innovators. For GMOs, these are governed by two separate directives (2001/18 and 98/44, respectively), and NGT supporters hoped that the patentability of edited plants could be debated separately at a later stage. However, in February 2024, the European Parliament introduced an amendment to the draft legislation to ban the patenting of NGTs. Institutional negotiations with the Member States are still ongoing, partly due to the European elections held last June, and partly because building solid majorities on these issues is no easy feat. Under Poland’s rotating EU presidency, however, some movement has started.

The Polish proposal suggests linking regulatory and patent status: NGT plants that are not patented could benefit from a simplified approval process, while those with patented traits would be subject to stricter rules. However, it’s doubtful this approach would prove effective. In practice, a research group or biotech company aiming to bring the edited tomato to market — a tomato that, biologically speaking, deserves deregulation — would have to choose between the easier route without patent protection or a tougher regulatory path with it. If the second path leads into the same regulatory black hole as GMOs, only non-patentable NGTs would remain viable, discouraging investment in the sector. It’s worth noting that non-EU countries that have already adopted favorable rules for the new techniques (like the United States and the UK) have not limited patentability, meaning the European adventure into agricultural gene editing would begin on an uneven footing. Some commentators have pointed out another issue: in cases of intellectual property disputes, the new framework — designed to simplify the system — might end up stalling it instead.

If the goal is to protect innovation without stifling it, a better compromise will be needed. To explore alternative solutions, one can look at the analysis published by We Planet, a network that aims to reconcile environmental protection with openness to innovation. They propose three guiding principles.

First: regulation must be as science-based as possible. The level of scrutiny for plants and foods should match the severity of potential risks, rather than be dictated by political or economic considerations. This is a basic principle meant above all to safeguard consumers and the environment.

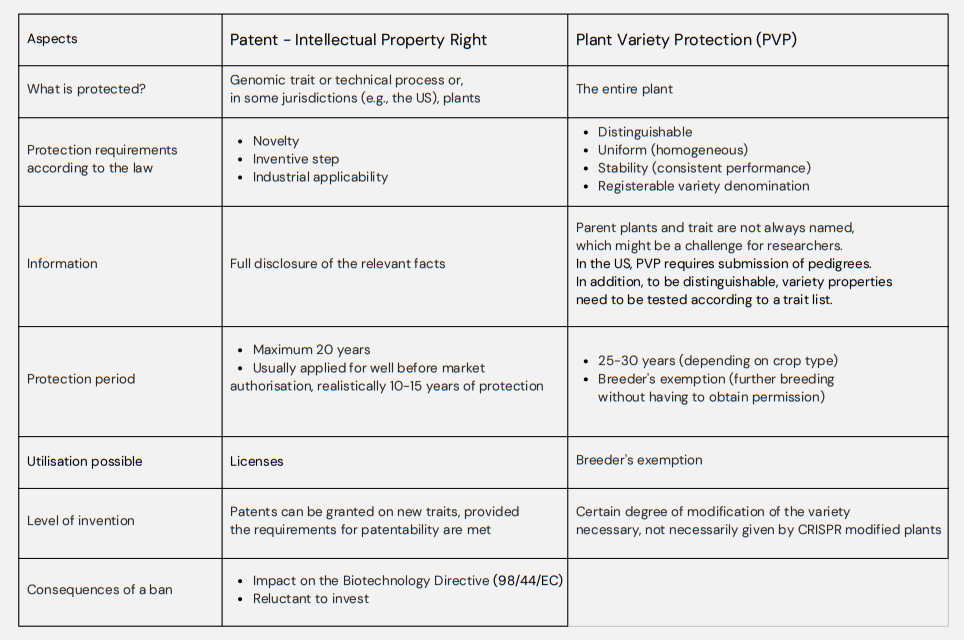

Second: innovation must be as fair as possible. The alternative system to biotech patents — plant variety protection (see the table below) — should be encouraged to ensure that public breeding programs and small companies aren’t left out.

Third: intellectual property must not create monopolies. Patents on new traits could be limited in scope to avoid blocking further innovations by third parties. Licensing platforms should be promoted to ensure fair access under reasonable terms.

[The table below, from We Planet’s Position Paper, shows the differences between the biotech patent system and the plant breeders’ rights system.]